All 902 letters: Mostly to his brother Theo, but a smattering of other notes to fellow artists and family members.

For even though Vincent is already dead during the time period of the book I’m writing, he is central to the entire story. My protagonist and real-life heroine is his sister-in-law, Jo, and how she persisted for fifteen years to save Vincent’s artwork.

Why did she keep going? It’s a question I’ve wondered about a lot. Some argue that Jo was simply being a good wife, following up on her husband’s dream. Others assume it was for her son—if she could build up the artwork’s value, then the value of her son’s inheritance would improve.

Yet, I couldn’t help believing that Jo had to have her own reasons.

For despite Vincent being a commercial failure, she saw something in Vincent--a man she’d met just three times-- that compelled her to dedicate her life toward making his paintings known. Sure, being married to Vincent’s brother Theo, and so having lots of dinner table conversations about Vincent would have influenced her, but I have some wacky relatives too—and I embrace their weirdness, but I’m not dedicating my life to them (yet).

So, guess what Jo did? She read Vincent’s letters. Put them in chronological order. Had selections of them published a number of times. And in so doing, gave us the gift of knowing what Vincent thought and felt and dreamed without ever having an inkling that one day his artwork would go on to impact millions and sell for millions.

Something in what Jo read caused her to believe in him.

Could I find it too?

So I began.

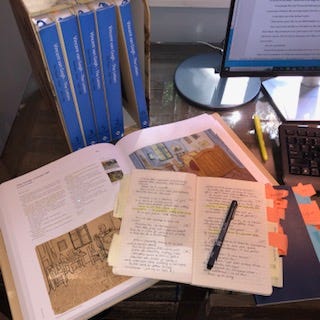

Ten letters a day

Reading the letters took me months.

My goal was to read ten letters a day, but I didn’t always make it. Just one letter could be several pages.

At first, I read like a researcher, finding insights I could thread into my story. But then, as I kept going, I began to think less of my book’s plot and drew closer to Vincent. There’s so much at stake. On the pages I see Vincent fail at being an art dealer, a teacher, a bookshop assistant, then as his heart yearns toward helping laborers and wants to serve them, I see his heartbreak at failing his exams to become a minister.

He's a loser. If he lived today and had that track record, I’d have thought he was a loser too.

His parents are embarrassed by him. His mental health is shaky. His father threatens to make him a ward of the court. I see the subtle switch in the letters from Vincent as the oldest sibling counselor to someone needing support. Vincent becomes melancholy and depressed when at the age of 26, and with Theo’s urging, he decides to become an artist.

It’s after this decision, like a train pulling out of a station, that the letters’ slow pace gradually take on increasing intensity and focus. There’s a thread in his letters. An artistic vision is accelerating, becoming clearer. It pulls at him. As he struggles to put it on canvas, his life hands him obstacle after obstacle to deal with.

Let me give you a taste of the ordinary man, Vincent:

Crazy in love

At age 28 Vincent falls head over heels in love with his cousin, a young widow named Kee Vos. She does not return his feelings. Nevertheless, Vincent relentlessly pursues her—even threatening to hold his hand over a candle until she sees him. Refusing to believe her resistance, he asks her to marry him. Kee responds, “Nay, no, never.” Yet, Vincent believes“…there’s a chance of a change of heart in Kee.” [Letter 179] Vincent! She said no.

Bites the hand that feeds him

Reprimanded that his drawings have no commercial value, Vincent hates art dealers, “the money men.” [235] When Theo starts work as a dealer, Vincent warns, “The thing is, Theo, my brother, not to let your hands be tied by anyone, especially not with a gilt chain.” [211]. Even after Theo is promoted to manager, in letter after letter Vincent drips disdain against Theo’s profession: “Dealers are rich; artists poor devils.” [236]. It’s “better to be a sheep than a wolf.” [409] He’s annoyed with Theo’s advice on how to improve his art “…not obliged to think of you as an oracle.” [432] Yet, Vincent is completely dependent on Theo for income and after insulting Theo would then end his letters asking for money. Vincent, be more politically correct! I imagine Theo exasperated, clapping his hand to his forehead. Yet, Theo still sent the stipend.

Fights back against imposter syndrome

Seized with doubt and discouragement, Vincent fights against his own inner voice declaring he is a loser. Again and again, he finds resilience. “I am a bull about being an artist.” [394] “If something in you yourself says, “you aren’t a painter”—IT’S THEN THAT YOU SHOULD PAINT.” [400] After making this statement in 1883,

Vincent would go on to paint another seven years until his death.

Sarcastic of studio artists

Vincent insists on painting out in the elements. Not by memory (he argues with Paul Gauguin on this) or by photograph or in a studio. Listen to his sarcasm in this letter to Theo: “I’m gripped by the thought that all these exotic paintings are painted in THE STUDIO. And just go and sit outdoors, painting on the spot itself! Then all sorts of things like the following happen—I must have picked a good hundred flies and more off the 4 canvases that you’ll be getting, not to mention dust and sand, etc—not to mention that, when one carries them across the heath and through hedgerows for a few hours, the odd branch or two scrapes across them etc. Not to mention that when one arrives on the heath after a couple of hours’ walk in this weather, one is tired and hot. Not to mention that the figures don’t stand still like professional models, and the effects that one wants to capture change as the day wears on.” [515] I just admire Vincent’s fortitude. He earned his paintings.

Heartbroken and guilty over the financial burden he was to Theo

In 1882 Vincent tells Theo he is “selling his work very soon to pay him back.” [394] Then the next year, “Probably get some income from my work soon.” [396] “ Three years later, “I don’t know how long, I’ll reach a point where I start selling. Hasn’t gotten what’s due him.” [551] In 1888,“ Feel to the point of being mentally crushed and physically drained, the need to produce, precisely because I have no other means none, none, none of every recouping outlay.” [711] Two years later: “Know that I’m trying to recoup the money that my training as a painter has cost, nothing more nor less.” [741] It never happens. I’m heartbroken when I read again and again how he hopes sales and acceptance are around the corner and I know he will not see it in his lifetime.

Do these snippets work for you? Do you feel you have a small sense of Vincent?

Did I find Vincent?

I started the letter-reading project to find the man behind the artist of today’s multi-million dollar paintings and splashy touring Van Gogh Exhibitions.

As I read, week after week, I saw him reflect a canvas of emotions: lovesick and excitable, despondent and resigned, angry and desperate, inspired and exhausted. He was a loser, an outsider, a pain in the neck. But above all of this turmoil, he was relentless. For years on end, he painted day in and day out, stopping only when poor health forced him. The ultimate underdog, he would not, could not give up on his inner need to create.

I couldn’t help but root for him. I recognized something in him that I believe is in all of us.

To close, let’s allow Vincent to have the last word:

“…feels by instinct, I’m good for something, even so! I feel I have a raison d’être! I know that I could be a quite different man! For what then could I be of use, for what could I serve! There’s something within me, so what is it!” [155].

What, indeed.