Historical Accuracy or Modern Relevance? The Writer's Dilemma

The Presentism question in historical novels

Digging in with Joan Fernandez is a weekly newsletter with ideas for you on shattering limits to reaching your true potential, told through bits from the life of Jo van Gogh (the woman that would not allow Van Gogh to die twice). Please sign up here.

Hey there!

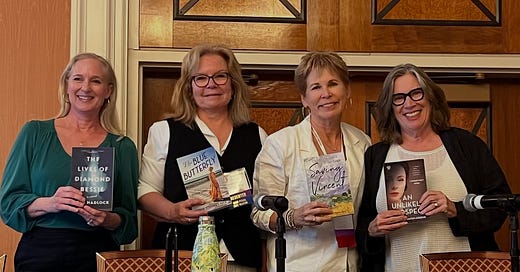

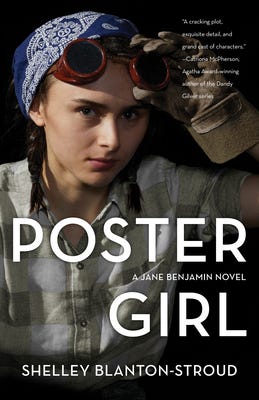

At the recent 2025 Historical Novel Society/North America Conference I had the fun of sharing ideas on an author panel. My sister panelists (left to right in photo) are Jody Hadlock, Leslie Johansen Nack, (me) and Shelley Blanton-Stroud.

Our subject was “‘Presentism’ and Writing Historical Fiction for the Modern Reader.” We defined “Presentism” as projecting one’s modern values and beliefs onto a past era.

We used several lenses to explore our topic—character agency, dialect and language issues, ethics—but in this essay I’d like to share an introduction to presentism and why it’s important.

First, presentism gets to the heart of the No. 1 question historical fiction book lovers ask, “How much of this story is true?”

Secondly, it’s a critical how-to writing craft topic for histfic writers because it brings up questions of integrity and choice. For the writer, decisions range from how much authentic dialect to include or whether to add a culturally sensitive issue to a story such as abortion.

There are no easy answers.

Let’s roll up our sleeves.

Differing Viewpoints

Our panel shared two sides of presentism:

Critics argue presentism compromises historical objectivity and prioritizes modern views over the views of that time period. Proponents say engaging in presentism can be an opportunity to make historical fiction more relevant and accessible to contemporary audiences.

It can be subtle or explicit, unintentional or deliberate.

Let me give you two examples using historical film and theater based on books since the productions are so broadly known.

A critic of presentism objects to the classic film, Gone with the Wind.

Released in 1939, the popular movie’s been widely criticized in recent years for its romanticized and inaccurate portrayal of slavery and the Antebellum South. It downplays the horrors of slavery, often depicting enslaved people as content and loyal, and promotes a nostalgic view of the Confederacy. Reflecting the then-modern views of the 1930’s, it’s a significant distortion of the social and economic realities of a specific historical period so a critic would say the film compromises historical objectivity.

In contrast, a proponent of presentism would applaud the musical Hamilton: An American Musical by Lin-Manuel Miranda, which opened on Broadway in 2015.

The musical is a deliberate modern take on historical events with its use of hip-hop, rap, R&B, and modern musical theatre styles, along with color-blind casting, to tell the story of the American Founding Fathers.

In this case, its use of modern musical forms and casting are intentional to make the historical narrative accessible to contemporary audiences, while also exploring themes of immigration, ambition, and legacy—universal topics relevant then and now. A proponent would applaud the musical’s connection with a contemporary audience.

Both these fictionalized historical accounts have garnered supporters and skeptics. Neither completely address the histfic fan’s No. 1 question, “then what parts of the story are true?”

Turns out, it’s not always straightforward to get to the heart of historical truth. For a good historical story isn’t simply a story about what happened, but why.

Let me illustrate with a little story from my grandmother.

The Story of the Whippersnappers

My grandma used to tell a story about the parade of young whippersnapper 20-something men who were hired to be her office boss in the 60’s and ’70’s.

She worked for a construction company as a senior bookkeeper. In her role, she had accountability for the day-to-day recording of financial transactions, maintaining ledgers, and balancing accounts. She loved her job and always wore heels, a suit and white gloves to work, and carried a big pocketbook.

In her eyes, over the fifteen years she held this job, the young men who were assigned to be her boss were a real aggravation. Unwilling to learn. Clueless and scatterbrained. Over the years it would frustrate her that the men would work for a while then inevitably move on, meaning she had to start all over training her next fresh-faced boss.

In response, my Feminist Self would hotly protest, “Grandma! Why didn’t you have that job! You should’ve been promoted!”

The first time I said it; I think it startled her. This idea that a woman could be a boss in an office was new. She’d internalized the societal idea that women couldn’t be leaders in business. Later, when she retold the story and I loyally chimed in with my protest (she knew it was coming) I wondered if I’d cast a new light on her experience.

Changed a scene in which she’d been proud of being an expert to one in which she felt cheated. If so, I’m not happy about that.

Then, too, maybe my objection affirmed her sharp intellect. She was a badass after all.

Meanwhile, who knows what those guys’ versions of that office scenario were.

Notice how in just this one situation, my grandmother, my interpretation, and those anonymous scamps all have different takes. It just goes to show that history in and of itself is not simply fact or truth, but perspective. The very same picture can be viewed entirely differently depending on who is telling the story and what they believe.

An historical novel could take any one of those perspectives and craft three entirely different points of view. All “accurate.”

That’s what Gone with the Wind and Hamilton both illustrate too.

Historical Records Reflect Bias

Back to our panel, we made the point that when it comes to historical records, there’s no such thing as truth or fact—because memory is captured through the lens of values and how that individual views the world, society, relationships.

For people like us who enjoy reading and writing historical fiction: This is table stakes. We’re aware that “official” history is recorded by the winners or dominant powers that have a political stake in casting history to support their point of view.

As stated before, this can be subtle or explicit, unintentional or deliberate.

Historical records reflect bias. Even primary research in which the author reads an individual’s diaries or journals may not be truthful. At the conference author Gill Paul recounted how when she was researching for her book Another Woman’s Husband she discovered Wallis Simpson lied in her diaries, stating she was not married when she and the Prince of Wales (later King Edward VIII) began their romantic relationship. Her divorce records show otherwise.

Leaving negative aspects out of our retelling of history can take away from appreciating the complexities of humanity. Another example from the conference came from author Renée Rosen who shared that when researching Fifth Avenue Glamour Girl she discovered cosmetic tycoon Elizabeth Arden had antisemitic sympathies. Rosen chose not to dwell on Arden’s racism, but not to cover it up either.

Interesting how history is recorded by omission as well as inclusion.

Notice too how seeing another point of view adds dimension and empathy. When my grandmother would repeat stories from her office role, I was sensitized to a woman in my family whose career had been cut off because of sexism. And for my grandmother, my response made women’s rights more personal, for she’d initially criticized Equal Rights Amendment movement for the protestors’ “un-ladylike” behavior.

We both saw another side of the picture.

Sweet Result

At the end of the day, the nuanced dance between historical authenticity and contemporary relevance, explored through the lens of presentism, is an ongoing challenge for historical fiction writers.

It’s wonderful when discerning readers understand that authors grapple with how much to integrate modern sensibilities into narratives of the past, especially since history is not a static collection of facts, but a dynamic interplay of perspectives.

Our panel’s hope is that the ongoing conversation surrounding presentism pushes historical fiction writers to do their work honestly to the best of their ability, inviting readers not just to understand "what happened," but to critically engage with "why."

In the end, if it helps us all feel more connected to people from both the past and in the present by building empathy—well, that’s a fantastic outcome.

Historical fiction at its best.

Warmly,

P.S. Have you ever read (or seen) an historical account you didn’t like because you felt it was too inaccurate? If so, tell me about it.

For fun insights into some of the authors attending the HFS Conference, check out

and her essay:. A Bunch of Historical Novelists Go to VegasMy Book

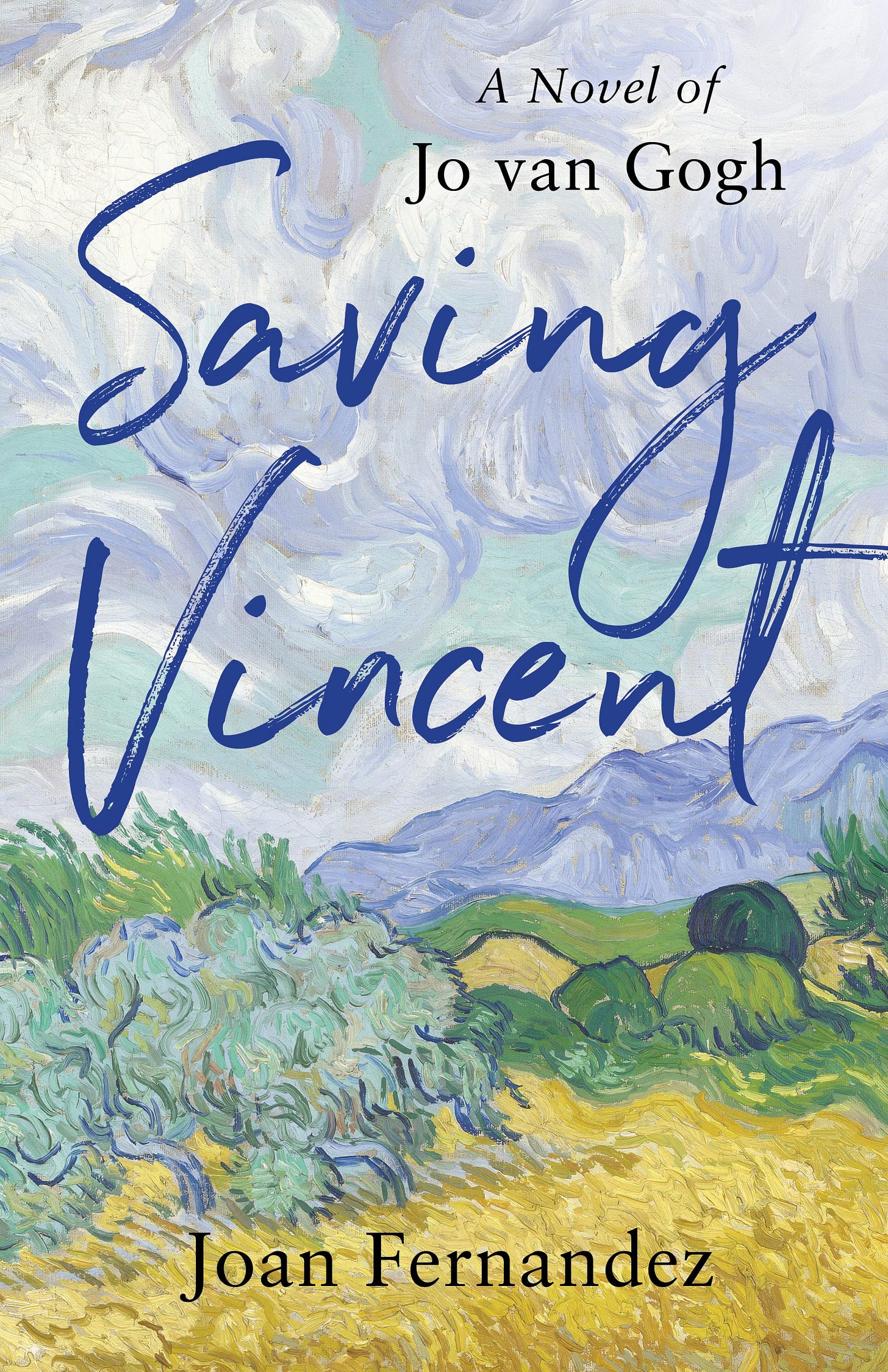

Saving Vincent, A Novel of Jo van Gogh, is about the woman that would not let Van Gogh die twice. This biographical historical novel is based on a true story.

In the early twentieth century, a timid widow—and sister-in-law of the famed painter—Jo van Gogh takes on the male-dominated art elite to prove that the hundreds of worthless paintings she inherited are world-class in order to ensure her young son will have an inheritance.

Grateful to be honored to win the 2024 American Writing Award in Art; the Bronze Award in the 2025 IPPY Book Award in Popular Fiction; and Finalist in the 2025 American Fiction Awards, 2025 National Indie Excellence Awards and 2024 American Writing Award each in Historical Fiction.

Buy Here

For book clubs and community groups looking for speakers, Complete this to connect and let me know your ideas of how I can share Jo’s story.

Book Recommendations for Books by My Sister Authors on the HNSNA Panel

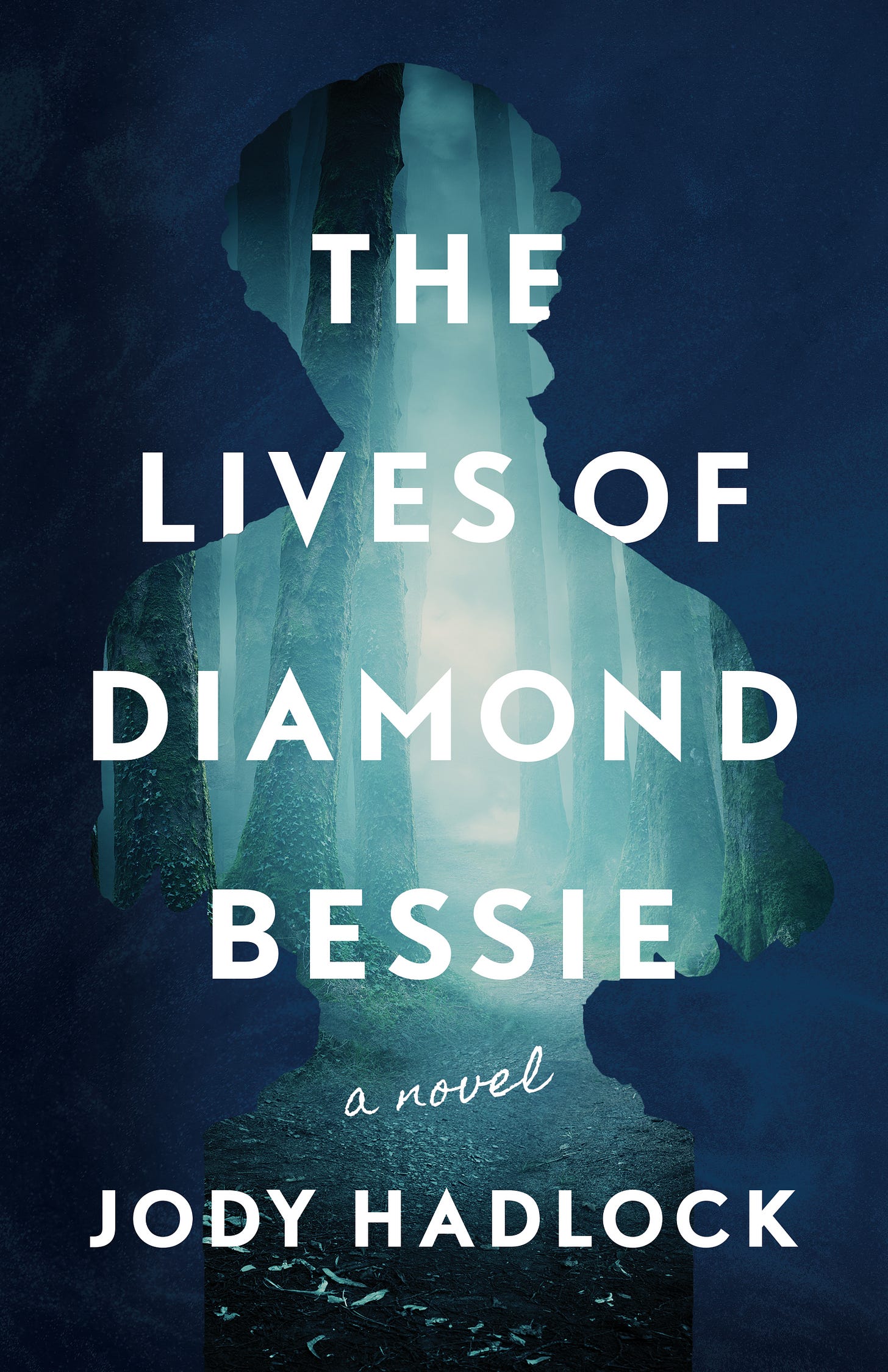

2023 Eric Hoffer Book Award Winner in Commercial Fiction

“[A] genre-bending debut novel. . . . There’s an impressive deliberateness in the way that Hadlock present her themes. . . The novel also skillfully uses foreshadowing to create a suspenseful atmosphere without giving the game away. . . . An often engaging and inventive character study.”

—Kirkus Reviews

Order on Jody Hadlock's website

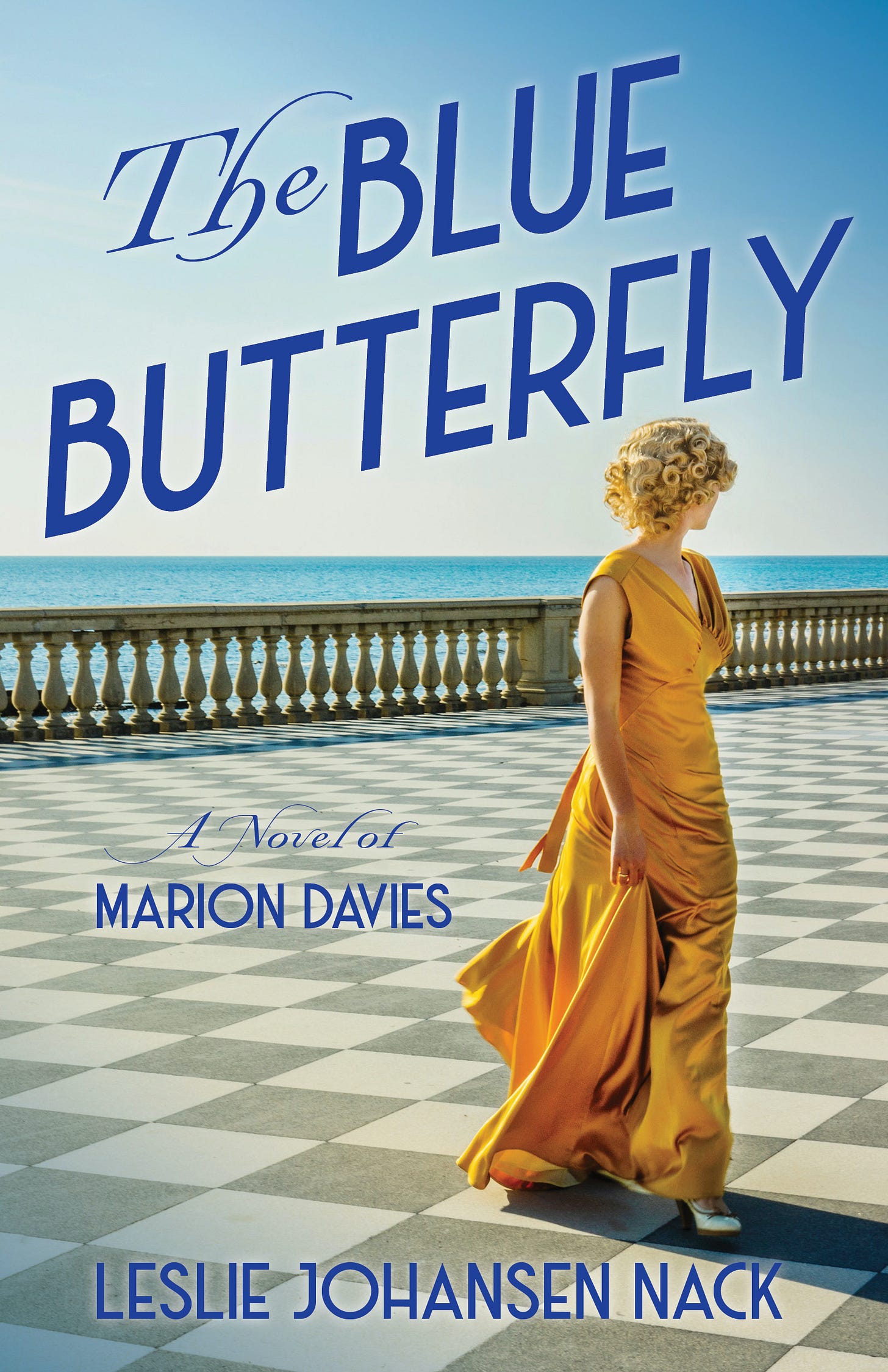

2023 IBPA Benjamin Franklin Awards Gold Medal, Fiction: Historical

“The book reads as if it really is Davies’ autobiography . . . . a timely reminder of what women would have been up against in Hollywood.”

—Historical Novel Society

Order on Leslie Johansen Nack's website

“Fans of Tracy Chevalier and Kate Atkinson will love being immersed in the detail-driven historical atmosphere, while hard-boiled mystery fans will thoroughly enjoy being led by our whip-smart and street-savvy heroine through the maze of clues leading to a shocking final plot twist.”

—Chicago Book Review, 5 stars

Order on Shelley Blanton-Stroud's website

I have to admit I'm a proponent of presentism in my own work, which leans commercial, and I noticed that one of the agents on the State of the Industry panel commented that presentism is fine so long as it is applied consistently throughout the novel. In this age where media channels are cross-pollinating, and print, ebook, audio, video, short-form video and all of that collide, I can appreciate both strict accuracy and presentism. I was shocked when Elizabeth I and Mary, Queen of Scots met in The Serpent Queen, but I was entertained, and the real facts were only a Google Search away. Call it speculative historical fiction if you will. And what about the modern take Shonda Rhimes has applied to Queen Charlotte? So commercial, and such a hit. This summer, I'm going to a museum exhibit of the Queen Charlotte costumes at a castle in Sweden, which Shondaland has taken on the road. The primary question you identify--what is real and what is not--should be welcomed by historical fiction authors, IMO. It's what we do. And then there's a great middle ground--what could have happened, but probably did not. Even the hyper-accurate Hilary Mantel suggests a series of mutual attractions between Thomas Cromwell and various women that aren't really supported by the record, but theoretically could have existed. And the series really seized on those hints in the book. I think supplying these elements added more than entertainment value, as the record is incomplete, and the man probably had emotional attachments, perhaps with different women than Mantel chose, of whom we know nothing. And, I really enjoyed your HNS panel showing that all these forms of our craft can coexist.

This is such an important topic, and people will no doubt be all over the map. Thank you for writing about it. I would have loved to be at the presentation. I am leery of presentism when it distorts what really happened. In a world where facts no longer matter, the line between fact and fiction is further blurred and impacts historical perspectives. We know two people can look at the same event and draw different conclusions, past or present. The point is they look at the same event, not different events. Yes, I know history was mostly written by white men (sadly), but when it's all we've got, it's all we've got. We can infer lost voices, of course, and we should. And we should incorporate new evidence, which makes history fluid and ever changing. That's exciting. Bridgerton and Hamilton, however, play loose with facts and present a slant that may help modern viewers feel good, but they do not illuminate history. They entertain.

Personally, instead of presentism, I appreciate it when historical fiction writers stay true to documented facts and build appropriate sensitivity into their stories. One of the finest examples of this among recent publications is Yellow Wife by Sadeqa Johnson. Johnson is a Black author, and she does not shy away from the horrors of slavery. She boldly uses the harsh, ugly language of the period. The writing is raw and gripping and hard to read sometimes. What I appreciate most is that she doesn't soften or sugarcoat this part of history. She doesn't try to protect modern readers or fear offending them. She brings them a powerful truth.

Am I for strict accuracy in historical fiction? No. It's, well, fiction. Writers have room to bend facts to serve a story. And part of historical fiction's role is to entertain. But I think it's really important to know how far to bend the historical record and to know and be clear why, or historical fiction writers may lead people away from a better understanding of the past rather than enlighten them, which feels irresponsible to me.